Like it or not, mosquitoes have arrived for the summer — and beyond their annoying, itchy bites, they also bring the risk of disease, most notably the West Nile virus (WNV).

Since the West Nile virus first entered the U.S. in 1999, it has become the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the country, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Reports of the year’s first cases are starting to trickle in from across the U.S., with 13 infections and counting as of June 13, per the CDC’s most recent data posted on its website as of Sunday, June 18.

WEST NILE VIRUS CASES, POSITIVE SAMPLES DETECTED ACROSS THE COUNTRY

Here’s what you need to know to stay safe.

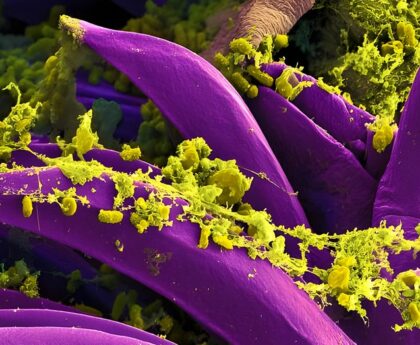

In most cases, the West Nile virus — a flavivirus in the same family as yellow fever, dengue fever, Japanese encephalitis and the Zika virus — is spread when Culex mosquitoes bite infected birds and then bite people and other animals, per the CDC’s website.

The virus is not transmitted through eating or handling infected animals or birds, nor is it spread through physical contact, coughing or sneezing.

One of the biggest misconceptions about the virus, according to Dr. Christian Sandrock, division vice chief of internal medicine at UCDavis Health Medical Center in Sacramento, California, is that humans are natural hosts or that they propagate disease.

“Humans and horses are inadvertently infected,” he told Fox News Digital via email. “This is largely a disease of birds and we can get infected, but we are not part of the host cycle.”

Although rare, there have been a very small number of cases when the virus was transmitted through an organ transplant, blood transfusion or from mother to baby during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

A vast majority — around 80% — of the people who contract WNV will not experience any symptoms, the CDC states on its website.

MOSQUITOES IN HOT WEATHER: THE MENACE YOU MUST KNOW ABOUT

“These people would only know there were previously infected if blood antibodies were checked,” explained Dr. George Thompson, professor of medicine at UCDavis Health Medical Center in Sacramento, in an email to Fox News Digital.

Around one in five people will develop febrile illness, which is marked by a fever along with body aches, headache, joint pain, diarrhea, rash and/or vomiting. These symptoms usually go away on their own, but some people may have lingering weakness and fatigue months after infection.

In rare cases — about one in every 150 infected people — the virus can lead to serious conditions affecting the nervous system, such as encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) or meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord), the CDC states on its website.

Those who develop serious illness may experience headache, stiff neck, high fever, disorientation, vision loss, muscle weakness, convulsions, tremors, coma or paralysis, which occur when there is viral infection of the central nervous system.

Those who have any change in personality or weakness of the legs and arms should seek medical attention immediately, said Sandrock.

RINGWORM RESISTANT TO COMMON ANTIFUNGALS FOR FIRST TIME IN US: WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT THE SKIN INFECTION

“It is possible to get some prolonged symptoms that can look just like long COVID,” he warned.

Among people who have this invasive form of the illness, around 10% will die.

While anyone can potentially develop severe illness, the highest-risk groups include those over 60 years of age, people who have had organ transplants and those with diabetes, cancer, high blood pressure, kidney disease, immune disorders and other certain medical conditions.

“The virus’ effects can be quite serious in the elderly,” Dr. Marc Siegel, a professor of medicine at NYU Langone Medical Center and a Fox News medical contributor, told Fox News Digital.

Those who think they might have been infected with WNV should be assessed by a health care provider, the CDC states.

Diagnosis of the infection can be made based on evaluation of symptoms, recent exposure to mosquitoes and testing of blood or spinal fluid.

OUTBREAK OF KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIAE BACTERIA INFECTS 31 PATIENTS AT SEATTLE HOSPITAL

There are not currently any medications or vaccines for the virus.

Health care providers will typically recommend treating symptoms with over-the-counter pain medications and getting plenty of rest and fluids.

Those who experience severe illness may need to be hospitalized for supportive care.

Since the first U.S. case in 1999, the West Nile virus has had a presence in the country each year. The number of cases fluctuates each year — from as low as 21 in the year 2000 to a high of 9,862 in 2003, per the CDC.

After a spike to 5,674 infections in 2012, annual cases remained relatively steady at between 2,000 and 2,600 between 2013 and 2018.

They dipped to 971 in 2019 and 731 in 2020, before rising again to 2,911 in 2021.

There were 1,126 infections in 2022.

“It’s hard to tell if it will get worse,” Sandrock told Fox News Digital. “But a combination of mosquito abatement practices (less of them due to funding and less public health focus), climate change and increased rainfall (particularly in the western U.S.) has led to the uptick in sampling.”

Another theory is that larger numbers of cases are seen in the wetter years, when there is a larger mosquito population, according to Thompson, who specializes in infectious diseases.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR HEALTH NEWSLETTER

“The dynamics are more complex than this, however — the amount of virus circulating in birds and even the current temperature are significant factors affecting the burden of disease,” he added.

Generally speaking, the number of infections is limited by the number of mosquitoes, Siegel noted.

In some parts of California, counties are using drones to apply larvicide in unoccupied marshes to reduce the mosquito population, he said.

“This approach is much safer than going after adult mosquitoes in terms of effectiveness, environmental impact and the affect on wildlife,” Dr. Siegel said.

Short of reducing the mosquito population, Siegel said the best modes of protection are to use insecticide, wear long sleeves and avoid going near standing bodies of water, such as ponds, lakes or reservoirs, where mosquitoes tend to breed.

Added Sandrock, “Mosquitoes bite at dawn and dusk, so be sure to wear long sleeves and use DEET during these times in July and August, which are the worst months.”

Article Source: Health From Fox News Read More